Asperen

Asperen is in the South of the Netherlands, Midway between Rotterdam and the German border. It was a small town in a rural setting by the river Linge.

Kees’s mother, Jannigje, grew up on a farm nearby went into service when she was nine years old. The family she worked for were farmers and she was said to have been treated harshly.

Kees’s father, Cornelis, was one of nine children. His father ran a carpentry business building wagons. He didn’t complete a primary education and could not read or write much at all. He worked as a labourer on farms in the area or building roads.

Kees’s father Cornelis and his mother Jannigje were from two different Dutch varieties of reformed church Gereformerde and Hervormde. Kees’s father was from the more stern tradition whereas his mother had a more liberal religious background.

Agatha recounted that members of Kees’s family including Jannigje, his Tante Pietje and brother Wout talked about Kees’s father fathering a son before he was married. Kees’s father himself did not acknowledge the child as being his. The alleged half-brother was said to share a distinct family resemblance. This contested fact was said to be at the root of a discontent that was evident in the relationship of Kees’s parents.

Jannigje was 22 when she was married in November 1915. Kees was born 29th July 1916. Kees was the eldest of the five children, after him came Wout, Aart, sister Alie and finally Jan.

Jannigje was 22 when she was married in November 1915. Kees was born 29th July 1916. Kees was the eldest of the five children, after him came Wout, Aart, sister Alie and finally Jan.

From an early age Kees had a strong connection with his aunt Johanna. She was a half-sister of his mother. On the de Jong side, we’re told that Kees’s father had been ‘bought out’ of the family and they ‘didn’t want anymore to do with him’. We don’t know exactly what resulted in that but it does explain perhaps how they were able to afford to buy a house.

When Jannigje’s brother, Kees, married Elizabeth ‘t Hooft (Tante Bet), Jannigje’s brother and sister apparently received a lot of money from her parents. According to Agatha, Jannigje resented that.

During the depression there was no work and they were very poor. They basically relied on what they could grow in the garden (they had an allotment outside the village). The winter of 1929 was particularly hard and Kees’ father was bedridden with pneumonia. The only musical instrument they could afford was a mouth-organ which he learned to play.

The family was very poor particularly in the early, pre-war era. They still had to get water from the town pump. Jan, said he was thankful Kees had championed the importance of education in the family. Whereas 90% of kids in the area went straight to work. Kees argued that they should be allowed to pursue further study (despite the fact that the family really couldn’t afford to support this). He argued that in the long run the benefit would outweigh the cost and though that mightn’t have transpired as quickly as they all hoped, you’d have to say by the 60s or so that decision was probably vindicated.

Jan recounted a story about how Kees bought a suit from Leerdam. His mother said he had to take it back though because it was not good enough quality and wouldn’t last. She said that he should wait until they had more money to buy a better one. The interesting thing about this is that the same story (but with a different spin) was told in connection with a picture of Kees sitting proudly in a suit by Janny the daughter of Ali: Janny said that her mother resented that Kees had bought a suit that they couldn’t afford and, after wearing it to church, Alie was the one who had to take it back to the shop.

Jan recounted a story about how Kees bought a suit from Leerdam. His mother said he had to take it back though because it was not good enough quality and wouldn’t last. She said that he should wait until they had more money to buy a better one. The interesting thing about this is that the same story (but with a different spin) was told in connection with a picture of Kees sitting proudly in a suit by Janny the daughter of Ali: Janny said that her mother resented that Kees had bought a suit that they couldn’t afford and, after wearing it to church, Alie was the one who had to take it back to the shop.

I remember Alie as a cheerful and loving tante when I met her in in 1968 but in her last years she shared primarily unhappy memories of Kees with me: It must have been a very tough time for all growing up and both Alie and Jan indicated that Kees was the apple of his mother’s eye and it sounds like girls weren’t offered the same opportunities for development in the family at that time. Alie talked of being so poor she would have to wear her brother’s swimming costumes to go swimming (which of course would be devastatingly embarrassing for a young girl I’m sure)

Alie also told a story about Kees arranging with Wout to carry the fishing gear to the river and saying he’d bring it back again but then not sticking to his word. Alie said she was sorry she didn’t have more pleasant memories of Kees to share. Kees used to enjoy fishing and there are quite a few photos of him in a boat. The fish would have been an important food source too.

Jan talked about how Kees (and Wout) had many years of unemployment after completing their training during the Depression. For a time Kees worked as a teacher voluntarily to gain experience.

Kees was required to do National service and had to go to Amsterdam for training. After a few days he feeling so down that he was sent home.

Surakarta

In Holland teachers were working full time for a quarter of the normal salary thanks to the Depression. The Reformed Church of Holland had a large mission area in Surakarta in Central Java, Indonesia. In Surakarta and Yogyakarta schools were plentiful. Schools with enough pupils and sufficient teaching standard paid qualified teachers a full salary.

When Mission Board in Amsterdam advertised for four male teachers and one female In May 1939, Kees applied and was interviewed and offered a position. They weren’t told exactly where they would be placed in Indonesia. The details of their positions would be decided when they arrived over there.

The group of four men and a woman (Agatha) sailed from Amsterdam on the Dempo in June 1939. Apart from Kees, the three other men were already engaged. He spoke to Agatha and we don’t really know what Kees thought initially but Agatha described their first encounters as clashes. She did find his eyes attractive. By the end of June she’d decided his voice was also quite nice. They visited Lisbon in Portugal. Then they stopped at Port Said and explored Cairo in Egypt. Next they travelled to Colombo in Sri Lanka.

They first arrived in Indonesia at Sabang, on the north-eastern coast of Weh Island, off the northern tip of Sumatra. It lies at the northern entrance to the Strait of Malacca and was the first port of call in the Malay Archipelago for vessels coming from the west. From there they travelled to Medan in Sumatra and finally arrived at Djakarta in Java in July after about a month of travelling.

Kees was employed in a school in Klaten. Klaten is South-west of Surakarta along the train line. He had good qualifications in English and Teach and so he was offered the position of headmaster when the current headmaster left. Kees boarded with a family while he was working there.

In the long July holiday of 1940 Agatha and a couple she knew, rented a house in Tawangmangu. Tawangmangu is about 40km east of Solo (Surakarta). It’s about 1300m above sea level and is a popular resort area because it is so much cooler than the city.

Their bungalow was on the slope of Mount Lawu and one morning the sun rose right over the peak. It looked out over the Solo valley. Two mountains; Merbabu and Merapi stood in the distance. The view was magnificent. The Merapi was a working volcano and at night you could see a glowing column rising from it. The place was quite expensive to rent and had lots of room so they asked some others to come with them. They asked a guy who already liked Agatha and then they also asked Kees. Agatha felt that Kees became more interested in her when he saw that she was being pursued by the other fellow.

The house belonged to a German painter who turned out to be a spy. He was interned after it was discovered that he had used the house as a base to send radio transmissions to the Japanese.

The walls were adorned with beautiful paintings. Compartments in the walls were filled with records. There was a record player you could take into the garden. Up to that point Kees hadn’t been exposed to a lot of classical music. That holiday they both enjoyed learning a great deal while listening to the collection of music. There were also games that you could play in the garden while you listened to music.

Kees, Agatha and three other men decided to visit the peak of Mount Lawu. The mountain is 3265m high. They started at 7pm by the light of a full moon and climbed for three-hours on small horses led by guides till they reached Cemoro Sewu at 1500m. Then they rested. They left the horses and continued on foot. It was another nine kilometres to the summit which they planned to do that in four hours. They walked for 50 minutes then had a 10-minute break.

It started getting cold, Agatha had a coat and a cape. Kees borrowed Agatha’s coat. During the breaks they all huddled together to keep warm. Kees grew jealous seeing Agatha in such close company with the other men.

In the hut, Agatha cooked the men some nasi-goreng. They had arrived too late to get a bunk and didn’t feel like sleeping anyhow so they all went for a walk with our guide.

The view from the peak was breathtaking and such an amazing contrast to Holland with its economic depression and flat countryside.

On the way down Kees and Agatha argued and Agatha walked the last part on her own. They didn’t talk at all the next day. Eventually things calmed down and they went for a walk together in the tropical forest. When they got home Kees helped Agatha take off her walking shoes. That intimacy marked the beginning of their romance in Agatha’s mind.

The prospect of war hung over their heads. Holland was already occupied. Yet the pair still had fun times together walking together into the mountains.

In October Kees was called up to the army and had to go to Malang for eight months of basic training. They were engaged in December, 1940. Kees knew his father would be proud of him for marrying a minister’s daughter but they had a lot of trouble contacting their parents to get parental approval. In June Kees returned to being the headmaster in Klaten.

Kees’s position was only temporary. He applied for a post as English teacher at the High-School in Tomohon in the Minahasa area of Sulawesi in Indonesia. When Kees heard that he had been offered the new position, they had to work out how to move and have a honeymoon at the same time.

They enjoyed some preliminary Javanese and Chinese traditional wedding rituals and pre-wedding parties with the Dutch community. They watched ‘Gone with the Wind’ the night before their marriage because they knew there wouldn’t be any films like that in the remote Minahasa area. Being set in the midst of the American Civil it was a foretaste what was to come.

On Tuesday July 1 1941 Kees and Agatha were married in Surakarta (Solo), Java in Indonesia. They had some Chinese girl attendants. They were sad not to have family there but the Dutch community was a close-knit group and they enjoyed their time. They were married in the Gereformeerde church. The church was full on one side with Chinese children and on the other with Indonesian students from their schools.

The first of July was the first day of the holidays. Their friends stayed behind for a few days instead of going straight to the mountains and came to the “open reception”. Instead of going to the mountains for a honeymoon and then coming back to pack, they decided to just enjoy a few quiet days in the town and then head off on their next adventure. It was a lovely house and overlooked the picturesque Sawas.

They went on a spending spree in a big department store and bought a 30 piece dinner service and other things they would need to set up house in Tomohon.

They travelled by train third class to Surabaya on the east coast of Java and stayed there twelve nights in a modest hotel (the trip was paid for by the government). Then they travelled for six days by boat. First they stopped at Makassar in Sulewesi where they stayed in a first class hotel.

They continued up the west side of Sulewesi via Parepare and Dongala to Manado in the Minahasa which took another six days. They went out on a boat with some local fishermen. They enjoyed themselves in the idyllic tropical setting and felt like it was a good way to spend their honeymoon.

They enjoyed exploring the new territory; wandering together down unfamiliar paths through lush green forests; finding special places for picnics and relaxing near cool mountain streams; wild and inquisitive monkeys chattered in ancient trees with leaves that played tricks with the light and shimmered in the evening sun after rain. The vivid colours of the flowers and the heavy scents of their blooms surrounded them. It was a blissful time. Everything they saw seemed to echo the love they felt. These memories formed the solid foundation of their relationship together. They took them with them to sustain them in the difficult and solitary times to come. These good times and shared moments of enjoyment tied them together forever.

Tomohon

In Manado Agatha’s teacher friend from Holland, Mandty, met them with her husband. They took us up to Tomohon; 1100 metres higher. They stayed there a week.

They had arranged to stay with a future colleague and his wife while they were house hunting. So, when school started on the 1st August they moved in with the Jan and Alie de Vries family and their six children.

They went looking for a home with Mandty and Martien’s assistance and found a timber house. There was a large middle class population, doctors, preachers and government servants who were mainly locals though some had studied in Holland. There was also a theological college with Minahassan lecturers. There was a Dutch Resident (Administrator) and the head of the Church was Dutch but townships each had their own “hukum kedua” (second law) chief.

In September their furniture arrived and they moved into their own home. They had furniture made in Surakarta (Solo) by Chinese carpenters according to Swedish designs that Agatha had been involved in designing which were made of beautiful jati hout (teak wood).

They settled down and the house slowly turned into a home. They bought a record player and ordered lots of books. Agatha paid workers to make a lot of improvements but they wouldn’t do anything without checking with Kees first. Kees thought Agatha might have been admiring some of the workers a bit too much.

According to Agatha Kees was an excellent teacher however, he had high expectations of his performance and was sensitive to criticism and antagonism. He started feeling low. Agatha looked for controllable reasons for these ups an downs rather than seeing them as psycho-chemical vissitudes. Someone told Kees they thought he would never make a good teacher, a student that didn’t like Kees and punctured the tyre of his bike. He wasn’t able to teach for a fortnight and was anxious about returning.

Kees was called to Manado for a fortnight’s revision with the army. The physical exercises in the open air and not having any responsibilities agreed with him and he felt better.

Kees was called to Manado for a fortnight’s revision with the army. The physical exercises in the open air and not having any responsibilities agreed with him and he felt better.

It was a very subdued group celebrated “Sinterklaas” that December under the shadow of war. It was held mainly for the children but the hearts of the adults weren’t really in it. The next morning they heard about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour. They all gathered nervously around a radio while the Dutch Governor General declared that The Netherlands was at war with Japan.

Kees left to be with his unit in Manado while Agatha stayed in Tomohon with Mandty who had moved in with her. Kees was conscripted into the Dutch army (KNIL service number 173216). The ‘Conscript Company’ consisted of about 200 men; fit but minimally trained. They were commanded by 1st Lieutenant F. Masselink.

Later that month, Kees sent Agatha a note to tell her that his unit was being moved to Tondano, and would pass through Tomohon on a bus. When the bus stopped Agatha and Kees hugged on the step of the bus (which they would never have done in peacetime). Kees sent messages to Agatha via messengers on motorbikes who passed her school. Kees had applied for a role as a motorbike rider but his night vision wasn’t deemed sufficient. Instead he was given a role in communications, manning the telephone and telegraph.

In the Christmas holiday Agatha stayed at Mandty’s in Langoan. From there she could ride a bike to Tondano where Kees was stationed. Japanese planes sometimes flew over with loud machine gun fire. Sometimes they sat on a jetty on the edge of the beautiful lake Tondano and talked and sometimes they found an abandoned house nearby.

For New Year’s Eve Mandty and Agatha baked 450 “olie bollen” for the soldiers but soon after it was forbidden to visit the Tondano camp. Fortunately, Kees was posted to the command post in Tomohon. Communications was his work from then on.

The Battle of Manado was a battle of the Pacific Theatre of World War II. It occurred at Manado on the Minahasa peninsula on the northern part of the island of Sulawesi (Celebes) in January 1942 as Japan attempted to open a passage to attack Australia through the eastern part of Dutch East Indies. Nobody had really expected the Japs to land on all those spread out islands. The fact that they did with the cost for the Japs of many troops and transports helped to save Australia from invasion.

Major Schilmöller used his strongest company, commanded by Captain Kroon, to defend the coast line of Manado Bay. Their left-flank was protected by a small unit (35 men) under the command of Lieutenant Masselink. Captain Kroon, was instructed to fall back to the Tinoör-stronghold, situated some five miles inland (half way to Tomohon), if he was in danger of being cut off by the enemy.

Kees had two days leave on the 10th and 11th. He and Agatha spent that time hiking; exploring the region; walking to Mount Lokon to the northwest and then to Tondano where they hired a room for the night in a guesthouse in Kakas on the shores of the lake. In the morning, while they were still in bed, they heard Japanese planes flying overhead. They didn’t yet know that in the early morning of 11 January 1942 approximately 2,500 Japanese marines had landed on two locations on the coast of Minahasa. About 500 Japanese parachutists came down at the airfield of Langoan from the planes they had heard.

Captain Kroon soon ordered his troops to withdraw towards Tinoör but he forgot to warn Masselink’s section and the crew of the 7.5cm gun. The crew of this gun managed to fire a few rounds at the landing enemy but was quickly put out of action. Masselink’s section also engaged the landing enemy. He recalled: “I fired at the landing Japanese, realising that I forgot to give my men the order to open fire. When I finally did so, we forced the enemy to take cover. Then they opened up on us with automatic weapons from a very short distance.”

Wanting to cover the withdrawing troops, Masselink gave his men the order to fall back towards the Manado-Tomohon road. Here he engaged the enemy again. During this fire-fight, Masselink could clearly hear wounded Japanese soldiers screaming for help. He continued: “While we held our ground, Kroon’s troops, in eight trucks, passed us and drove towards Tomohon. We kept firing till the last truck was out of sight and then, assuming that we had completed our task, I gave my men the order to withdraw to Tinoor.”

Captain Kroon got halfway to Tinoor. When he saw that Japanese troops were already in the area and realised that had lost control of most of his troops due to poor communication, he gave up the idea of defending the Tinoor-line and took the remainder of his company south to Koha instead. This left only five brigades, under Lieutenant van de Laar, to defend Tinoör. Masselink’s group joined them around 7am.

Four Japanese tanks appeared just after 10am. Three were put out of action by machinegun fire and a large tree, brought down by the KNIL troops on top of some of the tanks. The fighting at Tinoor lasted until about 3pm. The KNIL troops ran out of ammunition and had to retreat towards Kakaskasen (Just North-West of Tomohon). There they engaged the Japanese again. Sergeant Van de Laar wrote “These old warriors kept their high morale, though they never witnessed a modern battle before, and knew fully well that they didn’t stand a chance against this formidable enemy. Without orders from our commanding officer, we engaged the enemy time after time.” Van de Laar’s men put up quite a resistance with his company that first night and many Japs lost their lives at one strategic point on the steep road to Tomohon some 1100 m above sea level.

Kees and Agatha still didn’t know about the invasion. He knew he had to be back at the barracks by 12 midnight. They had a drink in the lounge and then headed back to Tomohon. At 10pm there was a loud knocking on their door in Tomohon and Kees was summoned back to the commando post. Kees filled his pockets with cigarettes, a photo of his wife and something Agatha had written to him. During the night, Kees was with the commanding officer. With the sound of machine guns in the distance, he received telegraph after telegraph. He put each one on a spike in front of Major Schilmöller but the command just stared at them, he did not know how to respond to them.

The next day they abandoned Tomohon and headed into the forest and spent the night there. Within two days the Japanese were in control of the entire area. The remaining KNIL troops were split into groups for the purpose of guerrilla warfare. Another de Jong was given orders to return to Manado and set the rice stores on fire. He was captured and decapitated. The results of this guerrilla warfare were limited: most groups surrendered immediately or were unable to fight for any length of time. Kees’s group received orders to make their way to Gorontalo; 400 km to the South-West of the island. For nearly a month Kees and his group walked and slept in the jungle and then rowed Southwards. When Kees arrived at Gorontalo, in February, it was already in the hands of the Japanese, the local Islamic people had no sympathy for the Dutch didn’t keep their existence secret and so they were taken prisoner.

From there they were taken to Manado. Kees spoke to a Dutch lady in Manado who was to be taken to the Women’s camp in Tomohon. Kees hoped Agatha was there. He said “tell my wife that I’m alright and that we will soon be together again.” There was a general capitulation of the KNIL in March.

Makassar

In April, Kees was taken from Manado to Ujung Pandang, Makassar in South Sulewesi. By April 1942 there were about 2,870 POWs concentrated in the infantry barracks. There were around 1,100 KNIL army POW plus about 1,700 Dutch, British and American navy staff, (survivors of the Battle of the Java Sea). In June and July 1942 small groups of POWs from the Lesser Sunda islands arrived.

The naval survivors were mainly English who had been picked up on the sea without clothes or possessions. When they arrived Kees overheard some of them curse “the focking Dutch”. Nevertheless Kees became friends with an Englishman, from Lancashire; Herbert Grimshaw. He was in the British Navy and was brought to the same camp after he was rescued after the sinking of the HMS Exeter in March 1942. Kees hadn’t had contact with many Englishmen to that point and they both obviously enjoyed discovering more about each other’s cultures. Kees particularly enjoyed improving his English. During this time he was reprimanded for acquiring medicine for a man with malaria without going through the proper channels.

In July (US Independence day) Kees wrote “Grimshaw has written a poem for me. I will let him write it in my booklet”. Herbert then wrote:

Recollections: dedicated to my good friend Mr C.A.de Jong, whose guidance and friendship I shall remember with gratitude.

When the sun rises, o’er Makassar’s isle

frequent surmises raise in me a smile.

To think of the days, most happy and free,

so will I always a friend to you be

You need not explain your disadvantage

I feel far from vain when my ills I gauge

If we two were free and gathered no moss

How strange it would be, how great thus my loss.

For we should never have met so it seems

yet I shall ever remember our schemes

to conciliate the Dutch and English

Why all this hate? Is this what we wish?

We will not digress, hate thrives in our fold.

This gross wickedness seems increased tenfold.

Yet, we are fine friends. Perhaps we inspire

in others, amends? Of this please enquire.

I am so grateful that you I have met

and ever thankful till my sun shall set

for all you meant to me throughout in these years

in my memory steadfastly adheres.

Remember those days we argued in vain?

Folks thought, from our ways, we were not quite sane

But we knew just the great importance;

discover we must the big difference

between you and me, your country and mine,

and so try to see some promising sign;

warmer unity, with each from now on.

Cordial entente between everyone.

As we found content, comfort, pleasure too

fond thoughts with intent I fostered for you

Succour and wisdom, honour, pure trust

when all’s said and done, confess it I must.

And you were not slow, not unresponsive

to the transient glow that my heart can give.

So think of me when the years have rolled on

and think of me then as more than “someone”

Think of me kindly and without restraint.

Seek such thoughts blindly, your soul they’ll not taint.

If, as mutually with mine, they remain

so eventually we’ll both feel the gain.

And what should befall, it matters nought

we shared each our all; such friends are not bought.

They staunched not their zeal, nor prevented the zest

for things they felt deeply down in their breast.

http://www.roll-of-honour.org.uk/j/html/jong-de-cornelis-antonie.htm

Kees also wrote in his booklet notes on his readings. These notes, roughly translations from difficult to decipher handwriting, nevertheless indicate a man finding solace in exploring the world of ideas and remembering love while physically confined. It was as though his physical confinement spurred him on to question the mental confinement of the conservative thinking that he had grown up in the influence of.

28th July, 1942:

“We have a beautiful library. Books collected from all sorts of houses. A great opportunity to enrich my spirit/mind. Just one of the many “lucky breaks” in an otherwise huge misfortune. Something fortunate amidst so much misfortune.”

“The new translation of the NT is beautiful.”

“I didn’t know that I was so stupidly conservative in the sense of being wary of the unknown, of new knowledge, a condition damaging to the expansion of the mind.”

“I had believed that all thought outside of the demonstrably necessary was useless. I believe now, that knowledge is the means to expand the limits of this prison in which my soul finds itself.

“Some fanatical democrats are dictators of the mind”

“Because some preachers of ‘Practical Christianity’ have rejected the source truth from which it developed, they have put off many people.”

“Only a Christian can be a socialist in any fundamental sense”

“Much wickedness can be mitigated by a large group of strong people drawing goodness/advantage from the evil.”

Hermine felt he was enamoured with Marxist writing and stated that he could not go back to the churches as they had known them in Holland.

29th July 1942 (birthday)

“Poetry is to life, as salt is to food”.

Kees made copies, in his characteristically neat hand, of some of his favourites; “Ballad” (T. Hood); the chorus of “Just a song at twilight” (Bingham) and Browning’s “If thou must love me”. He also wrote out numerous verses written by his new friend Herbert Grimshaw were written to a young lady called Dorothy.

Kees’ friend Herbert Grimshaw died of an illness in September. He was only 27.

In October Kees was herded aboard the Asama Maru 1 with about 800 other Dutch and British POW. It was a converted luxury passenger ship. In the Makassar Strait the ship was escorted by a Japanese frigate. Then it ship sailed without escort west of the Philippines, sometimes in zig zag course.

Japan

In a couple of weeks they arrived in the harbour of Nagasaki. One of the survivors of this camp, John Franken recounted these experiences in detail. Kees, on the other hand, said little about his experiences but he wrote a poem (original in Dutch; this is just a very rough translation)

Caught

Japs gather

Great misery

Flag displayed

We’re swept away

Prisoner of war

Home desire

Soulful song

You don’t forget

Working outside

You bring to mind

Milk and wine

or candy fine!

Discovered, smuggled

Crumbled amidst

Japs who strike

And the sickbay

Docked on ship

Farewells, suffocating

Course set to

Destination unknown

Struck by the cold

Emerging from the hold

Eyes slowly focus

On the land in sight

Stepping ashore

Times bleak, till now

You’d thought

it could not get worse

Nippon!

POW camp Fukuoka 2B was situated in the Kawanami company shipyard area on the island of Koyagi Shima in the Bay of Nagasaki. Here the POW were slave workers in ship building, ship reparation and dock building among the rock formations of the bay.

The extremes of temperature between the hot working environments and the cold outside couple with poor nutrition (two small cups of seaweed and rice for lunch) and hygiene meant many men succumbed to disease. Kees lived in a room with about 51 other POW. They slept in bunk beds

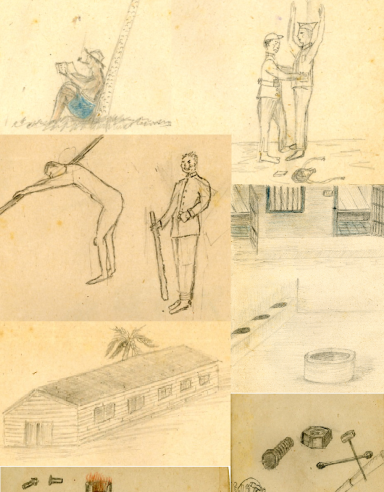

The few things that Kees let slip (e.g. his letter below), led me to think he was quite clever at finding a hiding place on the boats where he could avoid his riveting work. He used this time to draw some pictures of his equipment and guard beating a POW with a bamboo stick. He talked about how cigarettes were a currency among the POW.

It’s difficult to get a sense of those long years with such an uncertain future. Slowly changing seasons; bleak winters with disease and death, brutality with rare small pleasures in the form of Red Cross parcels.

This is another poem of his (again roughly translated from Dutch)

Closing song

Good night and to rest

Night watches, sleep softly

Then tomorrow outside again

Where the crows call “koera”

Good night and to rest

Sleep well, it brings strength

Because tomorrow will be hard again

In the cold, in the cold.

At least in March 1944 there was some hope when the first B29 bombers were heard. By June there began to be rumours of successes in Europe. Air raid shelters were dug into the rocky hills on the coastline.

In May Kees was moved with most of the other POW to work in a coal mine (Fukuoka 6b Mizumaki). They travelled, squashed together, in a train for 12 hours.

A flash seen to the north by those POW above ground on August 9 1945 turn out to be the Nagasaki atomic bomb. In the evening you could see a red glow in the distance. Soon after the Japanese surrendered. Then the Americans arrived to bring freedom.

By September they were able to leave the camp. The train went through Nagasaki and the damage was breathtaking. They were then taken to Manila.

Manila

When Kees arrived in Manila in October, Philippines he found out that Agatha was in Morotai because Dorothy Gnodde had enquired via the American command about Dutch soldiers who had been in Japan. So, he wrote to Agatha who was in Morotai, Indonesia.

Dearest Agaath,

Hello there, my dear little wife.

Until yesterday, I was quiet and patient, reading about all that is going on in the world, or listening to the radio. Then, yesterday evening, I heard there was a telegram, apparently saying you were on Morotai. Rest and calm flew away and I just wanted to go to you! Only five short hours of flying! Well, we’ve had to wait so many years, I suppose we can wait a few more days. The most important thing is that you are alive and I am too! I have never received any news of you Agaath, nor heard anything from Holland. I take it you didn’t hear anything of me either in all that time. Altogether I wrote many times and since the middle of August sent you several letters all addressed to you in Tomohon. So you will not have received those either. Now that I have the idea that you are close by, I’m having trouble writing things which are going to be easier to say in person.

I had so hoped that Alie would have received news of Jan’s passing but now I gather from the telegram that this was not the case. I pressed this point in all my letters to you, apparently in vain. This is a dark cloud hanging over the joy of the war ending, firstly for Alie and the children and also for us, don’t you think so? I’ll keep trying here to get the news about Jan out. See what you can do to tell Ali. Do whatever you think is best.

I was Jan’s “buddy” from the beginning in Manado, Makassar and Nagasaki. He was a friend, a father and a brother all rolled into one. Jan had such a firm faith that I never saw him down. On the wharves, amidst the most hellish noise he would be singing at the top of his lungs. He raised the spirits of many a lad who was down in the dumps. He belonged, as I did, to the few who did not fall by the wayside. On the contrary, Jan always looked great! He got really sick a couple of times – dysentery in Manado, malaria in Makassar and bronchitis in Nagasaki. Those were the times I could really repay Jan for all he had done for me. He usually recovered miraculously from those illnesses.

However, in Nagasaki, he had a lot of trouble with boils and that proved to be the harbinger of his ultimate fate. I often asked Jan if he needed blood, because I never had skin infections, but he would not hear of it. At the beginning of July last year he had a wound just below his knee accompanied by a high fever and on Sunday July 23rd [1944] at two o’clock he passed away. It was blood poisoning which went on to affect all of his organs.

That last week Jan did not speak anymore, but recognized me until the end, and squeezed my hand when some passages from Psalm 23 were read. In those last days he had the idea that Alie and the children were nearby.

Dear wife of mine, I long very much for news of you. I hear that Morotai lies in the flight path between Brisbane and the Philippines, so it must be possible to send and receive mail. Tell me honestly how things are with you. If I compare myself to others I have had unbelievably good fortune. I have remained well physically and mentally. I have, like Jan for example, squeezed myself as much as possible into all kinds of niches on the ships and have been assigned by the Japanese to do one or other job – metal working, deckhand, whatever, and in the evening still had energy left over to teach, read and study English.

Shortly before the atom bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, we were moved to a different camp on Kiushiu, a coal mining camp where fortunately we did not even need to duck. After the liberation we were fed and clothed by means of air drops. When we arrived back in Nagasaki, the whole city was gone. We were taken by cruise ship to Okinawa. From there in an amazing burst of air travel we arrived here [the Philippines] in 5 short hours.

Some of the friends I saw again were Arie Kuypers, Gijs den Dulk, and Habrie. VWPost who was reed thin and someone who I feared would not make it, came through okay, already sporting a widening waistline! Fortunately for me, despite the good food and not working, I have not added too much fat. So if your ideal guy is one with a jolly paunch I am sorry to disappoint you! There are still many things to say, some of which I already expressed in previous letters, but this page is almost full and I think that I’ll be hearing from you very soon and then I’ll write back or, if I can, come in person. Just five short hours away by air! You step into the plane, taxi for a while on the tarmac, then suddenly see everything becoming smaller, a short jaunt and then I’ll be with you.

Anyway, Agaath for now, much love and more love, your Kees.

Morotai – Tomohon – Morotai – Tomohon

Kees arrived by plane (a bomber) in Morotai on Friday the 12th October 1945 to be reunited with his wife.

They couldn’t stay in the women’s camp so they caught a transport to the reception camp. They arrived there at midnight and finally found a tent with 2 stretchers. Because they were relatively healthy they didn’t go to Australia to recuperate but stayed in their ‘‘new home’. They swam, walked, Kees taught Agatha chess and they watched movies in the open air theatre.

There was sadness too. It was a time of working out who was where and who was still alive and hearing about deaths. Agatha’s nephew, Anne had died on the Burma Railway. Kees happened to know that Ds. Hamel had been a chaplain in Burma. He had kept safe the diaries of soldiers who had died. Kees wrote to him and the put Agatha’s brother-in-law Jan in contact with him. As a result Teuna and Jan eventually received Anne’s diary. Agatha learned that a nephew of hers was shot in Rotterdam, and that an aunt was killed in Haarlem during a bombardment; and Kees heard that he had lost his brother Arthur in Germany.

Aart was not like any of his older brothers. He wasn’t so academically inclined. He had worked on a farm. The family said at first that the Germans had shot him, but this was story told apparently because they were embarrassed that he had worked in a German munitions factory. The story was unclear for many years; Agatha never really knew what had happened. Later they learned later that Aart died in an explosion in the munitions factory in November 1944 (WASAG Ungluck Coswig). There was some thought that the explosion was a result of sabotage.

During the German occupation, the Government declared that unmarried unemployed men who refused to work in Germany would no longer received (“Support”) benefit. The withdrawal of support was anything but an innocent action. For many families, this meant an immediate threat of penniless and inability to keep family unity. So, tens of thousands of Dutch boys were forced to work in Germany. His older brother Wout had tried to encourage Aart to jump from the train and go into hiding.

Jan told the sad tale of how they were sitting around the table when the minister visited the house to tell them about the death of Aart. He talked about how his mother knew something was wrong as soon as she saw it was the minister at the door. He talked about how it was for them not knowing what was happening with Kees in Indonesia/Japan.

Once some Americans let them borrow a rubber dingy. They were having fun. The water was very clear and they enjoyed looking at the fish and the coral. Then Kees decided he wanted to swim so he jumped in. Agatha tried to stay with him and Kees swam as best he could but the current was strong and the gap just increased. Finally, Agatha found a position in the rear that made it possible to paddle better. She rowed like mad and they finally closed the gap. Kees climbed in and collapsed exhausted in the boat and they just drifted for a while. Then they slowly rowed back together. It would have been ironic to survive prison camp just to drown in paradise.

When they Dutch camp was ready they moved in there. They lived in a tent about 100 metres from the seashore. Each day they could walk and swim. It was idyllic. One night, as they were walking, they saw what looked like a burning bush. It was a tree full of thousands of fireflies and looked spectacular.

Nick van de Post had already returned to the Minahasa to start the Junior High School which was a church run school. He asked Kees to join him. They were tempted to apply to go to Australia but, being healthy, Kees felt obliged to help out. They didn’t want Agatha to go at first but Kees and Agatha would not be separated so Agatha was allowed to accompany him and teach as well. So, they left Morotai in November 1945.

From the airfield they were taken to the church’s complex where they stayed a few days until they could find a place to live. They were reunited with their friends Mandty and Martien who were taking care of Freek de Kok’s three girls; Marga (4), Riek (6) and Hilda (8) while he was Australia getting organised.

Kees started teaching and they found a lovely native timber chalet in the Kampong in Tomohon looking out over a fishpond. The three girls moved in with them when Mandty and Martien needed to go to Australia to recuperate. They were excited to have the children with them for Christmas. So they decorated a tree with red gerberas, chillies, baubles made out of cotton wool and candles in candle holders made from tins. Kees was so excited he insisted on waking children up at 12 midnight to see it.

Indonesian Independence had been proclaimed just after the Japanese surrender. The declaration marked the start of the diplomatic and armed-resistance of the Indonesian National Revolution, fighting against the forces of the Netherlands.

In March 1946, the Minahasa joined the rebellion against the Dutch; the Permuda uprising. Dutch men were imprisoned in Manado but Kees, in the kampong, missed out. The school they had started already had lots of pupils and they were all very keen to learn. Still, they were alarmed by the revolution happening around them and, concerned for their safety, they were thinking of packing their bags and leaving.

Pastor Wenas, head of the church in the area that ran the school, came to beg Kees to keep teaching. The resident (administrator of the area) and van de Post the headmaster of the school told Kees that a thousand permudas (revolutionaries) in the school were better than a thousand permudas on the street. Kees wanted to refuse but they were persistant. He gave Agatha a gun and taught her how to use it. They took their guns with them and opened the school.

A week later though, in the middle of the night, Dutch officers came to our home and told us to pack only necessities as they had to leave there and then. They stood at the harbour waiting for a boat. It was supposed to be women and children first but when they saw that Nick van de Post was already in a rowing boat going out to the freighter, Kees joined Agatha and the children in their tiny rowing boat. It nearly capsized on the way. The freighter took them back to Morotai. Again they left everything behind. The girls were upset and couldn’t understand why they had to leave their dolls.

They went back to living in a tent next to the beach enjoying another month in paradise. The three de Kok girls were flown to Australia to be reunited with their father and his new partner.

After a month they received a message from the school saying that they wanted Kees to go back to Tomohon. When they were told it was safe they caught a freighter back to the Minahasa. They started teaching at the Church’s MULO (Junior high school). Kees went teaching Geography. Agatha stood in for him sometimes despite some people’s disapproval. There were many pupils there. They came from all over including the surrounding islands. Classes from could contain a hundred or more students. There was hardly any paper, and no books, but they were keen. Some sat on the floor and then fainted because of lack of oxygen.

Things went reasonably smoothly for the next year. There was still quite a bit of political unrest and in some areas it was unwise to travel unaccompanied. They took their walks in a large group for safety someone would be specifically assigned to keep an eye on the children. Generally though, they got on well with the students. Many of them had missed out on some of their schooling due to the war and they were now in their twenties. They were back at school trying to make up for lost time.

They had waited a long time for a baby. Finally, in 1947 it seemed like that would happen. Agatha had to stop teaching because she felt constantly sick. By the end of the year the combination of continuing political unrest, Hermine’s impending birth and their general health made them feel it was time to return to Holland.

In December they travelled to Jakarta where they stayed with Agatha’s sister, Hermien who was also expecting a child. From there they caught the Willem Ruys back to Holland on the return leg of its maiden journey.

Holland

Kees and Agaath took 16 months leave to spend some time in Holland to see their families and meet the in-laws they had not yet met since their marriage in Indonesia and the ensuing war. They alternated staying with each of the families, travelling by train. First they went to Kees’s but Agaath’s mother wanted to be there also to see her daughter.

It wasn’t spoken of a great deal but there was a sense of social disparity between the Minister’s family and the de Jong’s. It was surprising to Agaath that the de Jong children generally worked out as well the more she learned about the difficult circumstances they experienced during their upbringing.

Kees’ mother and Wout had decided who would sleep where in their tiny house. Kees slept downstairs in the “bedstead” (cupboard bed) and Agaath’s mother had to climb a ladder staircase each night to get up to the attic where she and Agaath shared a bed.

When Agatha met Jannigje she sensed a lot of resentment, the result, no doubt, of many years of struggle and poverty that Agatha couldn’t relate to. Agatha’s couldn’t understand why Jannigje professed being stupid and refused to join in games but then often answered the questions before other people.

Alie was an ambitious girl. When Kees left for Indonesia she was just sixteen. During the war she had started to work on a farm like her brother Aart. Alie would bring home fresh milk and eggs from the farm. She had hoped to become a hairdresser but her father had discouraged her. He told her that such thoughts were just vanity. After the war she decided that she would like to be a midwife. Agaath supported her in getting her father to give his permission. She was also clever but her parents were old fashioned in their ideas about what a girl should do. She enjoyed a long career in midwifery.

They visited Kees’s Oom Kees and Tante Bett and heard the sad story also of Kees’s cousin Wouter de Adel who committed suicide. He had been accused of being a collaborator with the Germans. They also enjoyed some afternoon teas with Kees’s aunt Johanna who he had always liked growing up.

Jan and Agaath got on well. People were generally impressed with his manner. He was only 18 and had grown up in difficult circumstances. As a baby his mother had trouble feeding him and he went to live with his Tante Bet and Oom Kees. Jan was in teacher’s college at the time, following in the footsteps of his Kees and Wout. According to Agaath, Jan fitted in much better than Kees with the Koers family in general (particularly Co) though Kees and her mother took to each other from the start.

On Kees’s return from the war, Kees and Jan cycled down to Belgium together. They asked a farmer if they could sleep overnight in his barn (in the hay) and, after confiscating any matches, he said okay. In the morning they were offered some bread and butter. Jan recounted how there were some ‘insects’ had got on the butter and he said to Kees “you can’t eat that”. But Kees, after his camp experiences, had no qualms eating it.

Hermine was born Agatha’s mother’s home in Noordwijk aan Zee in March 1948. They enjoyed the tulip fields near Noordwijk together. Agatha’s eldest brother Henk had a good business and offered Kees a full-time job in his company. He hoped that Agatha would stay in Holland for their mother’s sake. Kees couldn’t imagine himself as being a businessman and refused. It was his intention to return to teaching in Indonesia. He liked the climate better. It was a point of contention between them.

Hermine was born Agatha’s mother’s home in Noordwijk aan Zee in March 1948. They enjoyed the tulip fields near Noordwijk together. Agatha’s eldest brother Henk had a good business and offered Kees a full-time job in his company. He hoped that Agatha would stay in Holland for their mother’s sake. Kees couldn’t imagine himself as being a businessman and refused. It was his intention to return to teaching in Indonesia. He liked the climate better. It was a point of contention between them.

They travelled again to Asperen with Hermine. Agatha liked to walk with Kees’ sister Alie on the dike of the Linge where you could see the orchard blossoms. Kees kept studying and then passed an exam that qualified him to teach English in Senior High Schools and Teacher colleges.

They travelled again to Asperen with Hermine. Agatha liked to walk with Kees’ sister Alie on the dike of the Linge where you could see the orchard blossoms. Kees kept studying and then passed an exam that qualified him to teach English in Senior High Schools and Teacher colleges.

The Minahassa was a centre for education and was still growing. Kees received a telegram asking him to resume teaching in the Teacher’s College in Tomohon. They were building a house for them but it wasn’t yet ready. Kees departed on his own at the end of May 1949 for Indonesia with the plan that Agatha and Hermine would follow later.

A few months later Kees telegrammed Agatha saying that he had booked passage for them on the Willem Ruys to Indonesia. They left Holland in November.

Tomohon

Agatha arrived in Djakarta and stayed with her sister who also had 19 month old baby. When she’d been there two weeks her brother-in-law took told her that Kees was in hospital suffering from depression. Instead of going by boat to Manado, he arranged for a plane ticket. The doctor agreed to let Kees go with her to stay at a friend’s place overnight.

Hermine was nearly two. She hadn’t seen her father for six months when she was only 14 months old still, she recognised him, her little face went all red and she let herself be hugged and kissed which was unusual for her.

Agatha moved into their new house while Kees went back to the hospital. A neighbour’s wife had helped Kees make things ready and welcomed them. Agatha was pleased to find rattan chairs, a cot for Hermine, beds for them and three servants; Clara (again), Maria and Cornelius (13). The house had no plumbing so Cornelius would go to with a yoke with two big tins to fetch water.

Kees came home from hospital. Agatha’s luggage including linen, towels and crockery arrived. They enjoyed a very festive Christmas dinner with friends. Kees felt a lot better and returned to work and things went smoothly for a while.

Kees came home from hospital. Agatha’s luggage including linen, towels and crockery arrived. They enjoyed a very festive Christmas dinner with friends. Kees felt a lot better and returned to work and things went smoothly for a while.

One day after siesta, Agatha opened the blinds and saw people burning books in the outside area. The servants were very upset and told them that the Javanese army had occupied the Minahasa.

Again, they were told they had to leave their house. They moved to a large pavilion but it was very dirty. Agatha and Clara spent the next two days scrubbing walls and floors. Still it worked out all well. It had its own bathroom and a large garden for Hermine to play with her little friends.

They spent another year in Tomohon. 1950 was a strange time. The town felt unfriendly but, hiking in the country, people were friendly. When the adults went hiking, mothers took turns to stay behind and mind the children. The Dutch grew closer but they were slowly leaving. Finally the political situation deteriorated to the point where it was impossible to stay. Once more they were forced to leave our home and move in with friends.

Students from college came to help us move. The Minahassers weren’t keen on the Javanese occupation. They were sorry to see them go. They were keen for locals to finish their training and become teachers themselves.

They auctioned their possessions to help finance setting up somewhere new. Talking to their friends, the Tillema’s, they discussed migrating to Australia. Agatha would have preferred to return to Holland. Kees and Ann joked about finding gold. Ann wrote to her friends who were already in Australia. The friends encouraged them saying “You will have to work hard and you won’t be rich but your children will have a good future”.

Kees and Agatha also wrote to a seaman Agatha had met on HMAS Westralia while she was chaperoning children at function. They asked him for more information about Australia. They wrote back with information about house prices and the cost of living. They said it was likely that Kees with his knowledge of the English language would be allowed to teach. Kees though had decided that he wanted to have a break from teaching.

They decided to go. Despite Agatha’s preference she could see some advantages. Australia was warm, the families in Holland were so different, and Kees wanted to be away from that. Ironically Kees’ family felt that Agatha and influenced Kees to move to Australia.

It was difficult to get their documents together for the passport. Kees had sent his birth certificate and marriage certificate to Djakarta to organise superannuation. So they had to organise for witnesses to their wedding to attest to it. This was sufficient for the passport but not recognised in Australia.

When they talked about how they would live in Australia they assumed that Agatha would also work in whatever job she could get. However, when Hermine was nearly 3 Agatha found she was pregnant again. Still they both loved children and were happy about that. Preparation though was hampered as Agatha felt quite sick for the first 6 months. On her good days she packed while Kees ran around booking passages and assembling papers.

Although they loved the country and got on well with their students and locals in the Minahassa, they were relieved to be leaving Indonesia. It was getting quite difficult for the Dutch. Kees was told that he had to use Indonesian while he taught English in the Indonesian junior high school. There had been cases of people with guns coming to the houses of the ‘blandas’. They flew to Manado and rested a few days. Then they travelled by KPM freighter for three weeks.

Djakarta

It was Christmas 1949 when they arrived, they stayed in a safe place near Agatha’s sister, Hermien. Public guesthouses were dangerous and people were robbed there. Cor was well respected so they were somewhat protected. Hermine and Tjaco enjoyed that month together.

They had 400 hundred pounds of their own and before they left Hermien and Cor lent them another 50 pounds. Cor and Hermien and little Tjaco waved goodbye to them in Jakarta on the 19th of January 1951.

Kensington – Bathurst

They flew on a bomber and had a brief stop in Darwin before landing at Kingsford-Smith on the 26th of January 1951. They enjoyed looking at the red country they were flying over. It was stunning. They both felt very positive. In Sydney were herded into a bus that took them a hostel in Kensington. It felt a bit like being in camp again. They ventured into the shopping centre to buy a raincoat for Hermine as it was raining heavily.

Early next morning, Saturday, they drove them to Central station and put them on a train to Bathurst. For breakfast they were given a cold spaghetti sandwich, which Agatha, on an empty stomach, six months pregnant, didn’t find at all appetising. Kees’s first impression, as they pulled out through Redfern and Newtown was of very poor looking corrugated iron hovels unlike the images they had imagined. Once they got out of the city however, the train ride was a joy and they enjoyed looking at the beautiful open country.

They were taken to Bathurst Migrant Camp which had been Army Barracks during the war. There were 11 blocks most of which were subdivided into two room sleeping quarters. There were shared toilets, showers, laundries, kitchens and dining halls. There was a picture theatre with seating for 1,800. There was also 150 bed hospital and a post office with telegraph and phone services.

They had been told they would be sleeping in separate Men’s and Women’s areas so they were very happy to be allocated a room which had 2 beds and a cot. When they were in their room they danced for joy. They got used to eating mutton but didn’t get used to the flies.

They had been told they would be sleeping in separate Men’s and Women’s areas so they were very happy to be allocated a room which had 2 beds and a cot. When they were in their room they danced for joy. They got used to eating mutton but didn’t get used to the flies.

A bus took us them to visit a church in Orange and after that they went to a family’s place for a meal. The differences in culture and the fact that they were strangers made it feel strange although they appreciated the gesture. Agatha had to walk along a track into town for prenatal check but they were enjoying all the unfamiliar birds and flowers.

They stood in line for food and they were quite happy with it. Some complained it was too fatty. It was the first time they’d eaten a large steak with a big rim of fat, mashed potatoes and salad. In Holland meat was rationed. They carried their food back to their rooms trying to protect them from the flies.

Agatha was taken hospital by an ambulance after she had an attack of pain, nausea and blacked out. Her gall bladder was apparently having problems adjusting to the diet. Agatha thought fasting would be the answer. The doctor said she thought that the baby was coming. She stayed in hospital for a week with Hermine and liked the treatment she got there.

When Kees started working in the Steelworks he travelled from Wollongong to Bathurst each weekend. He bought Agatha a Bakelite radio for a week’s wage (13 pounds). Agatha thought it was a waste at first but soon found it was great for both entertaining and improved her language and understanding of Australian culture.

During the week, Kees stayed with the Moerman in Corrimal. A lot of fibro houses were being built there; whole streets of them. Kees wanted to buy one and he told Agatha to move there. A family had said they could stay with them. Agatha was reluctant; she really wanted have her baby in the small hospital with the sisters she knew and Hermine had whooping cough. But the family assured her that their child had it too and they were concerned that if they didn’t do it then they might have to wait a long time.

Corrimal

They moved to Corrimal in March and slept on the kitchen floor in another Dutch family’s house while they arranged the purchase. Kees negotiated the loan. They were able to afford the £500 as a deposit with the aid of a loan from Agatha’s sister Hermien. They bought 42 Railway Parade (aka Duff Avenue). The land and house together were £2200. It was a fixed interest rate and they paid £11 a month mortgage and insurance. The house had three rooms, a dining room and kitchenette.

It was only a five-minute walk to the beach. Behind the fence was the railroad track and, in the background, Broker’s Nose, the mountain that had beautiful purple colours in the morning.

They started with an empty house with just a gas cooker. They enjoyed having hot and cold running water in the bathroom. The loo was outside in those days. The steelworks gave Kees quite a bit of overtime and he would come home at about 10pm. They bought a dining table and chairs, a bedroom suite, utensils, crockery, pots, pans, a cot, a pram and a bassinet on hire-purchase. Agatha had been handed down sufficient baby clothes from friends so they felt ready for the birth of their second child.

Kees went to the corner shop one night and heard about a Dutch couple living in a tent with two children who were ill. He asked Agatha if she’d mind if they moved in. The Timmermans had also arrived from Indonesia and Tim also worked in the steel works. They were good company and became like family; minding each other’s kids. Tim was a musicophile and on Sunday mornings Beethoven’s music reverberated through the garden. He was also a photographer and developed photos in a tent in the backyard. The garden was large and they all worked on it to keep them in vegies and strawberries. In this pre-sewer era, if the outside toilet started to overflow, Kees would dig a big hole in the backyard.

In April 1951 they didn’t yet have a phone or a car. When the labour began it was night. Kees had to wake the neighbours to use their phone to call a taxi. Arthur was born the next morning in Wollongong Hospital.

In August that year they received a telegram saying that Agatha’s mother had died of a stroke. When Kees heard, he remarked “She had a lovely character. I wish I had her childlike faith.” Kees and Agatha liked the Dutch Minister who was at the Presbyterian Church. They helped with the Youth Fellowship and sang in the choir. Kees would take Hermine to Sunday school while Mum looked after Art and Nick. Hermine admired his acting chops and his handsome appearance as he taught a lesson about doubting Thomas. She would wave to her Daddy when the train passed on his way to work.

On weekends, they’d all walk down to the beach together with children in prams and on shoulders. Then there was often icecreams and in the eventing a fish and chip feast.

By 1952 they realized they were expecting their third child. They decided to have another room built and they still let the front rooms. The new room had French doors to the garden and it had morning sun. The Timmermans moved out before Nick was born. Over the next few years they had three more Dutch families stay with them. It helped with furnishing the house. Nick was born on Kees’s 36th birthday.

Kees became president of the Dutch club which was flourishing with the influx of new arrivals seeking fellowship. They organised concerts and dances. He also had leadership unofficially as the person with best grasp of English. He liked to help people out with their tax returns and other challenges they had settling into a new country.

One Dutch friend had a terrible accident at the steelworks. He was badly burned. He survived but he lost a leg. BHP offered him compensation of £1000 plus medical costs and he asked Kees if he should accept. Kees explained to him how much he should have; based on how much potential earning he had lost through the accident; he could never do the same type work again, and he was in the middle of building his own house. Kees worked with a lawyer and argued that he should receive at least £11,000. The lawyer laughed but when Kees presented him with all the facts and calculations he said ‘Well, we can try’. They were awarded the full amount.

In February 1953 a major flood of Holland was caused by a high spring tide and a severe European windstorm in some locations the water rose to nearly 6 metres above sea level. A large portion of Holland was underwater. The Dutch Club in Australia organised a collection of donations to send back to support the one million homeless people.

The Illawarra Daily Mercury reported later that month, “The President of the. Dutch Community (Mr. C. A. de Jong) said he was most moved at the spirit evidenced by the meeting. ‘On behalf of the Dutch people, I heartily thank you for your interest.’ He said. ‘For 2000 years we have fought the sea and have turned many acres of the sea bed into fertile land. Now the sea has had its revenge. One-sixth of all Holland is submerged. We cannot assess our loss. One million people are homeless. With the assistance of Australia and other free nations, we feel sure Holland will still survive. We already feel at home here; now we feel, even more, that we have real friends in Australia.’”

Agatha and Kees were asked to talk about their POW experiences on a number of occasions including a dinner of the Christian Business Association in Wollongong. After that I decided not to do it anymore; Kees didn’t really like it whereas Agatha felt it was therapeutic. Agatha and Kees sometimes laughed about the funny things that had happened in camp but it was never something that Kees could see as a positive experience unlike his wife.

They enjoyed walking down to the beach for a swim. They had their hands full with 3 children under five and still no washing machine or fridge. Still, Kees was feeling up and told Agatha about Scottish family where the wife had TB and couldn’t care for her 9 month old baby, he suggested that they take care of the child. Agatha agreed as long as they could get a washing machine to help lighten the load. Diane stayed with them till she was 18 months old.

In 1954 Kees was told he would receive superannuation from his time in Indonesia until he was fifty (Australian income was subtracted from the amount). They received £600 back pay to start. They paid back Agatha’s sister and contributed the Kees’ parent’s income. They bought a second hand fridge, an electric lawn mower and a piano. Other people thought they should buy a car but the public transport was not bad and Hermine was showing signs of being quite musical.

The choirmaster at church was also the local inspector for education and he convinced Kees that he should teach again as there was a great shortage of teachers so Kees sat for an exam (grammar and spelling) and passed without any trouble. So, in 1955, (now called Con by his colleagues) began teaching again.

In Towradgi there were many migrant children. Kees handled that well after an inspection he was promoted to deputy headmaster. Unfortunately he had troubles with his boss, a new rule said you had to be naturalized to make promotion and Kees was promptly demoted. Kees was feeling down. There wasn’t much suggested by way of treatment. They attributed the depression to being a POW and suggested a few beers would help.

It was a difficult time while Kees had some time off work and there wasn’t much sick pay. They had some superannuation from Holland. Agatha did some private tutoring until Kees recovered and returned to work.

A Dutch lady wanted tutoring to prepare for an English exam and Kees didn’t want to teach just her so he suggested Agatha prepare as well. So he helped them both reach the required standard. He encourage Agatha to accept a teaching position in 1957.

Kees was working in Fairy meadow in the boy’s section. They were on holidays in the Woy Woy area when they heard that his father died in September. Kees was feeling down. When he recovered he wanted to go back to Holland where his mother was now on her own. They began to save and put the house on the market. When they found to their surprise that they were expecting their fourth child, the idea of returning to Holland evaporated. They bought a TV as their children were spending a lot of time watching tv at the neighbours.

When Kees returned to teaching he was feeling up and he heard an acquaintance had a wife who was ‘in service’ with a Dutch family and wouldn’t let her and her two children leave. He asked Kees to go with him in his truck to get his wife. They turned all turned up that night and stayed for three weeks. The lady was a cleaner and helped Agatha who was debilitated with morning sickness. After they left she continued to come in once a week to help out.

Kees was enjoying his teaching. He got on well with his boss. He also taught migrant classes at night while they saved for a car and maybe a trip back to Holland to see their families. Walter was born in 1958. Life was good. On Sundays they visited all the sights and parks in the surrounding area that they could reach without a car. Hermine was doing well in high School.

When they bought their first car, a Standard 10, it enabled them to start exploring this wild and old country with its beautiful beaches. The three bigger children would sit in the back and Walter would sit on Agatha’s lap in the front while Kees drove. They had another holiday in the Woy Woy area in 1959.

Kees was still assistant teacher and his excellent headmaster wanted him to become deputy so he urged Kees to become naturalized. They no longer planned to return to Holland so it made sense. Their Indonesian marriage certificate wasn’t recognised, so they had to get new birth certificates and then go to Canberra to get an Australian marriage certificate. It all took a lot of walking. They joked that this was their third marriage. In November 1959 they went to Wollongong for the ceremony.

After this, both Kees and the headmaster expected Kees to be automatically reinstated to his position as deputy; it was still the same inspector who’d done his previous inspection and yet he had to go through the whole rigmarole of inspection again. Kees felt humiliated but subjected himself to it. When all that had passed it was announced that Fairy Meadow would become a demonstration school, Kees refused the honour and so did his boss.

April 1961, on the same day they heard about the Bay of Pigs, Arthur fell off a see-saw and broke his arm. They had a holiday in Lake Conjola. Kees liked to take the kids out fishing in the boat. They visited surrounding areas too including Mollymook. Later that year they holidayed in the Woy Woy area for the third time.

Kees began teaching at Wonoona. In 1962 Agatha heard of the death of her brother Nanne. Kees had a lot of pain and finally had a kidney stone removed at Bulli hospital. He was stressed starting at a new school and then his mother died. He had another depression. Agatha hadn’t yet returned to teaching after Walter but did teach migrant classes and some other private tutoring and there was some money from the Dutch Super. Walter went to Kees’ school a few times and enjoyed playing with the marbles and other things that had been confiscated from his pupils.

Kees would take Walt down to the beach to play; digging tunnels and sticking lighted matches in them and playing Noughts and Crosses with matchsticks. The library was in town and there was a park in front Kees would watch Walter on the play equipment there.

On Kees and Nick’s birthday in 1963 Walter ran into a wooden swing in Austinmer park and broke his jaw. Kees and Agatha had to leave the other children in the care of friends and drive up to try to find Prince Henry Hospital. Agatha stayed in Sydney while Walter was in hospital and Kees had to keep an eye on the older children. When he helped Walter going to sleep he’d put the sheet over their heads and his hand would try to get in pretending to be a spider.

In 1964 Hermine was in her final year at high school, Walter started school and Agatha returned to teaching. Kees enjoyed football and took his kids to Thirroul to watch it. They all travelled up to the Easter show. Kees had a minor collision in the Standard 10 and they decided to buy a new car. They bought a Ford Falcon.

They knew that Hermine would do well and want to go to university so Kees got a move to Bexley as Deputy Head and they prepared to move to Sydney.

The bought a block in Lugarno and had a Lend Lease house built on it.

Narwee

While the house was being built they lived in Narwee. They only had a two-bedroom flat to accommodate the six of them. The parents slept in the opklap bed which they pulled down at night to sleep in.

On the weekend we’d generally travel to Hurstville where the kids went to church. We’d all stock up on books to last us the rest of the week. We’d hope in the car and visit the sights of Sydney like Warragamba dam and the Royal National Park.

During this time Walter had another accident with his toe and ended up in Canterbury hospital for six weeks. Agatha was finding working in Panania difficult. Kees drove her there and picked her up in the afternoon.

Lugarno

They were very glad to have more room when they moved to Lugarno. They also got the phone on. There was lots of lovely bush around us. Kees always enjoyed nature and with the Georges River and the Lugarno Ferry that they could walk to easily it soon felt much saner.

When Hermine handed been keep up to date with her assignments she wanted to opt out of Uni. Kees wrote to the Uni asking for an extension. Hermine got back on top of her studies then. She moved closer to the university staying with a friend of the family.

During this time Kees and Agatha liked working together on building the garden. Kees would take the family to the beach at Cronulla. The boys were keen on surfing so they put racks on the car. They explored places like Wattamolla in the National park as well as all the Southern beaches. Oak Park was their favourite ultimately. Kees mainly enjoyed floating on his back and doing a bit of backstroke but he was willing to be a shark and attack Walt on the li-lo. Kees did a good organising games for the children at Walt’s birthday party in 1966. He taught Walt to play chess.

They had holiday and stayed a colleague of Kees’s at Wyongah. They had to drive up to Taree to attend a wedding of one of Mum’s colleagues. On the way back it was raining cats and dogs and a Citroen, which Mum and Dad allege didn’t have its lights on, crashed into us from the right so Kees was judged to be in the wrong. Later that week Kees backed the Falcon out of the driveway into a policeman’s car across the road.

There was the usual arguments and teenage door punching at the time. Dad wanted the boys to try harder at school. It was a stressful time too knowing there was a chance Arth and or Nick would be conscripted into the army to serve in Vietnam. Kees had a stroke while he was driving to Bexley one night in December 1969. He had to pull over after he lost the use of his left arm temporarily. He went into Prince Henry Hospital where they were able to clear the blockage. Kees was feeling down and had some time off work. Thankfully the Dutch-Indonesian super they received was quite helpful. Kees had a tradition of providing haircuts for his boys.

Despite all this Kees assisted convincing the Dept of Education to offer Arthur a teaching scholarship. He liked to bring home teaching aids and practice science experiments with Walt.

In March 1970 he worked again. He became so well that he too decided he’d like to visit Holland himself. Hermine left to travel to Europe in 1970. Kees went to Holland soon after and he saw Hermine there and had his turn to visit his siblings.

In March 1970 he worked again. He became so well that he too decided he’d like to visit Holland himself. Hermine left to travel to Europe in 1970. Kees went to Holland soon after and he saw Hermine there and had his turn to visit his siblings.

At the end of the year Kees, Agatha and Walter went to the snow and stayed a Buckenderra Caravan park on Lake Eucumbene where they enjoyed exploring the environs including Canberra. Kees and Walter started getting interested in looking for gemstones together. They’d picnic by creeks and enjoyed trying to identify rocks they were collecting.

At the end of the year Kees, Agatha and Walter went to the snow and stayed a Buckenderra Caravan park on Lake Eucumbene where they enjoyed exploring the environs including Canberra. Kees and Walter started getting interested in looking for gemstones together. They’d picnic by creeks and enjoyed trying to identify rocks they were collecting.

Kees, Agatha and Walt visited Blackheath and stayed in a house that belonged to Mum’s boss’s family. During the day they went on walks and in the evening they played Monopoly near the open fire.

In 1971 Arthur and Nick both left home and began Teacher’s College and Hermine had found David and gone straight to the US to be married. Kees and Walt travelled south together and camped at Kiama and then at Kangaroo valley looking for gemstones. Later in the year Agatha joined them and went on a road trip North in 1971. Agatha had her license by this time. They stayed in Flotilla Lodge at Elizabeth Bay for a week. Arthur came up to join us for a while. Then they drove the station wagon further north, sleeping in the back or staying in caravans and travelled up as far as Yamba.

I only recall one time that Kees used corporal punishment. Walter continued to ride his bike down the hill in a dangerous way after it was forbidden, Kees was forced to discipline him with the aid of his belt. He took Walt to a father and son night and did his best to provide some basic instruction in the area of procreation. He started to get pay Walter to do a few of the gardening chores like mowing, laying a drainage pipe and painting.

Kees returned to teaching in Peakhurst South for a while before taking a medical retirement. In the Christmas holidays that year Agatha joined them and they travelled south again. They camped in Kiama, Bendalong and then Pebbly beach. Kees and Walt were still interested in finding gemstones together. The weather got quite bad. They went as far as Bega and then decided they’d had enough and turned around.